Dev Update: Integrating Thermodynamics

It's getting hotter

When I started working on thermodynamics for “Rocket Science” I couldn’t even imagine how deep a rabbit hole. I am close to a finish line and now I understand why some recent space simulators choosed a very simplified model of thermal processes. Because everything appeared to be much more complicated compared to what I described in the previous dev update. Since I’ve spent so much time doing research and solving equations, I will publish most of my findings in this article despite the fact that each formula in the text reduces the number of readers by a factor of 2. First of all, it could be verified by people who have knowledge in this field (feel free to correct me in the comments below if I made a mistake). Secondly, I hope it will save some time for developers who want to implement a similar system in their game in the future. And finally, I’ll be able to refresh my memories in a couple of years because by then I will have forgotten everything. Also, worth noting that all the equations in this article are just very simplified approximations made for the game, that need to be computationally fast.

Thermal radiation

So I’ve begun with thermal radiation since it is a primary mechanism for heat dissipation in space and the Stephan-Boltzman law formula looked not so complicated. But as I mentioned in the previous update all thermal equations need to be solved in such a way so they become a function of time. This is the only way to support a time warp. And I absolutely needed to make it work during time warp for all spacecrafts because simulating it only for focused spacecraft or only during physics simulation was out of the question.

The way to make those equations as a function of time is to solve a differential equation relative to time. Initially I thought that I could find already made solutions. But in most cases there weren’t any or they were in a papers locked by a paywall. So I needed to do it myself and my calculus skills were very rusty because I haven’t done this since my time in university.I’ve spent a couple of days re-learning calculus and solving various examples. And I felt confident enough I returned back to thermal radiation.

\[\begin{equation} T = \left( \frac{T_{0}}{\sqrt[3]{\frac{εA}{mC_{m}}σT_{0}^{3}t+1}} \right) \label{eq:thermal_radiation} \end{equation}\]A temperature change due to thermal radiation, where: \(T_{0}\) is the rocket part starting temperature in Kelvins, \(A\) is the total area of the part in square meters, \(ε\) is the part thermal emissivity, \(m\) is the mass of the rocket part in kg, \(C_{m}\) is the body’s thermal capacity, \(σ\) is Stefan–Boltzmann constant, \(t\) is time. Note, that the ambient temperature not accounted there. More on that in the next article.

But before I could apply it I needed to introduce a lot of missing parameters to rocket parts. For example, just for thermal radiation every rocket part needs the following stats: temperature, exposed to space area, thermal capacity, emissivity and of course mass. Only the mass is currently in the game. While some params like thermal capacity could be set depending on what I want to achieve, others need to be calculated. Like area, which directly depends on the shape of the part. And I can’t use the area previously calculated for aerodynamics, since it is projection to the side of the cube area and I needed a true one. Thankfully, this one was relatively easy to solve. I just calculated the area of each triangle for each mesh for the rocket part and summed them up. And then repeated for each rocket part currently in the game. Unfortunately I couldn’t fully automate this process like I did it for aerodynamics (those part processing you see every time a game starts for the first time after each update), because Unity then will consume two times more memory for each part mesh which is not acceptable.

One of many tools I did for this update

One of many tools I did for this update

It doesn’t take that long, but it is a very routine process: put the selected part in a special tool, press a button, get an estimated area value, write this number into part config, repeat this process for 150 parts…

Finally I got all the data I needed, solved the differential equation and got \(\eqref{eq:thermal_radiation}\) as a result, put everything into a new thermodynamics system, set the initial temperature of the rocket to 293 K and launched it into space. To be honest it was very satisfying to watch how the whole rocket and each rocket part are slowly cooling off. It was only a tiny and easiest piece of the puzzle and it took me almost a week to finally add it to the game. But it was totally worth it.

Solar irradiance

I decided to implement solar thermal radiation next. This one depends on distance to the Sun and it can’t be solved as a function of time because of orbital mechanics. But the distance to the Sun changes drastically only during interplanetary transfer and you can integrate it with a pretty large time step. But there are two problems with this approach: the orientation of spacecraft and a planet’s shadow. See, I decided to calculate incoming solar radiation depending on what side the spacecraft faces the Sun. The larger an illuminated area, the greater incoming heat flux. But this has the same problem as with solar panels. On big time warp steps it would underestimate or overestimate received heating and electricity depending on orientation on sampling point with the exception of the case when the Sun set as target and spacecraft pointed to it. The same goes for the planet’s shadow. Spacecraft could be outside or inside of the shadow in every step which will yield inaccurate results. I haven’t solved this problem yet, but it is not that critical and I will find a solution in the future.

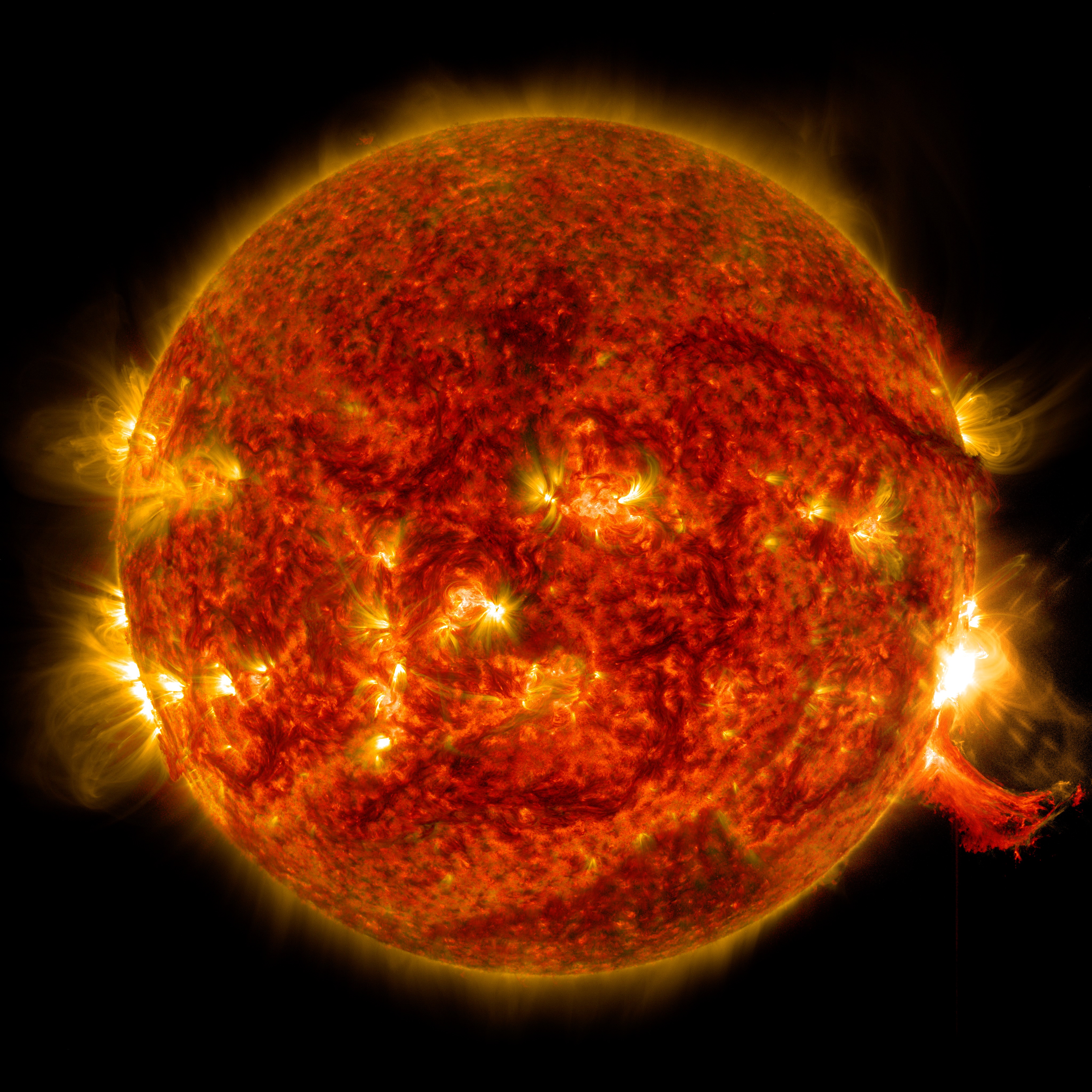

The source of many heating problems in space. This image was captured by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on January 5, 2023.

The source of many heating problems in space. This image was captured by NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory on January 5, 2023.

To approximate lit surface area I used the same technique as for aerodynamics. I approximate each rocket part as a cuboid, where the area of each face equals the projected area of the rocket part onto the corresponding cube face. Then you can easily use dot product between cube normal and the direction to the Sun to find the amount of incoming light. And the amount of heat flux from the Sun is calculated using the same Stefan–Boltzmann law, since the Sun can be modeled as a black body.

\[\begin{equation} Q_{s} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}A_{i}max(N_{i}\times L, 0)aε_{s}σT_{s}^{4}\frac{R_{s}^{2}}{D^{2}}dt \label{eq:solar_irradiance} \end{equation}\]where: \(Q_{s}\) is heat flux from the Sun, \(n = 6\) is the number of cube faces, \(A_{i}\) is the face area of cuboid approximation, \(N_{i}\) is the cube face normal to the Sun, \(L\) is direction from spacecraft to the Sun, \(a\) is the part thermal absorption coefficient, \(ε_{s} = 1\) is the Sun emissivity, \(T_{s}\) is the temperature of the Sun in Kelvin, \(R_{s}\) is the Sun radius in meters, \(D\) is the distance to the Sun in meters.

After adding temperature change due to solar irradiance using \(\eqref{eq:solar_irradiance}\) I observed how the spacecraft reached the thermal equilibrium at around -50 C° on the low Earth orbit. It was cool to see how the temperature drops every time the spacecraft enters the Earth’s shadow. And then heat up on the dayside of the planet. But what I also immediately noticed, that all the parts have very large differences in temperature depending on its mass and area. This was fine, but the temperature should slowly even out. And I suddenly realized I’d completely forgotten about thermal conduction inside the rocket.

Thermal conductivity

I’ve spent another couple of days researching and solving equations. And I needed another two parameters for parts: thermal conductivity and connection area. I tried a more simple implementation at first where parts would transfer heat to an abstract “rocket” and then “rocket” would redistribute the heat to every part back. This worked well and was very fast in computation, but I was not satisfied with the results. Imagine a long spacecraft that for some reason heated on the one end. I wanted to see how heat slowly flows from one side of the spacecraft to another. And simplified calculations obviously couldn’t give that. I’ve sat down and implemented this properly, so every rocket part transfers heat through attachments via conduction to every other part. And I also made it in such a way, so it would work fast and scale well with the large number of parts.

As for the equation, I reached a limit of my solving skills. Resulting equations gave me strange results: parts transferred heat too quickly or too slowly. In the end I found an approximation that produced satisfying results, but probably not entirely physically correct.

\[\begin{equation} T_{y} = T_{0y} + \left( T_{x} - T_{y} \right)\frac{m_{x}C_{mx}}{m_{x}C_{mx}+m_{y}C_{my}}\left( 1 - e^{\frac{a_{y}t}{1.5 + \frac{m_{x}C_{mx}}{m_{x}C_{mx}+m_{y}C_{my}}}} \right) \label{eq:thermal_conductivity} \end{equation}\]where: \(x\) and \(y\) denotes parameters of parts with higher and lower temperatures respectively and \(a_{y}\):

\[\begin{equation} a_{y} = k\frac{A}{LmC_{m}} \end{equation}\]where: \(k\) is thermal conductivity, \(A\) is the cross sectional area, \(L\) distance from the attachment to the center of part.

To test it out I turned off radiation heat transfer, made one part very hot and launched a rocket. And it worked as expected: over time all the temperatures between the parts equalized. At the same time, the average temperature of the rocket didn’t change. But there was a problem with the time warp. The conduction equations had e in power of time and some other variables. And with the time warp above 1 hr per second this value overflowed. The only solution was to split the time step in segments of one hour, calculate heat transfer for each of them and then sum up the results. But you can do this up to one day per second. After this, computation becomes expensive. So, on the last two time warp steps this calculation would be performed only for one day per second. I think this is fine, since it is just a heat transfer between parts and no energy is gained or lost during that.

Re-entry heat flux

It’s time to finally get down to what it all started for. The bad news is that incoming reentry flux will depend on spacecraft orientation relative to the velocity vector and the surface area exposed to air flow as it was in the case of solar irradiance. The good news is that these calculations should be done mostly inside the physics simulation, because the game always switches to it when a spacecraft enters the atmosphere. So I don’t need to solve the differential equation this time. I plugged Sutton Graves formula I mentioned in the previous dev update with some additional modifications, including the same cuboid approximation I mentioned before:

\[\begin{equation} Q = \sum_{i=1}^{n}A_{i}max(N_{i}\times F, 0)k \left ( \frac{p}{R_{n}} \right )^{0.5}V^{3} \label{eq:aerodynamics_heating_flux_sutton} \end{equation}\]where: \(F\) is the inverse direction of airflow, \(k\) is the constant specific to each atmosphere (1.7415e-4 for Earth and 1.9027e-4 for Mars), \(p\) is air density, \(R_{n}\) is the effective radius of the part, \(V\) is velocity of spacecraft.

I’ve also set a temperature limit for rocket parts, after reaching which the part would explode. The last step was to finish the re-entry shader I made while researching this topic last month. Then generate a bunch of blob meshes, put everything together and then spend several days tweaking material parameters, until I will get an acceptable result.

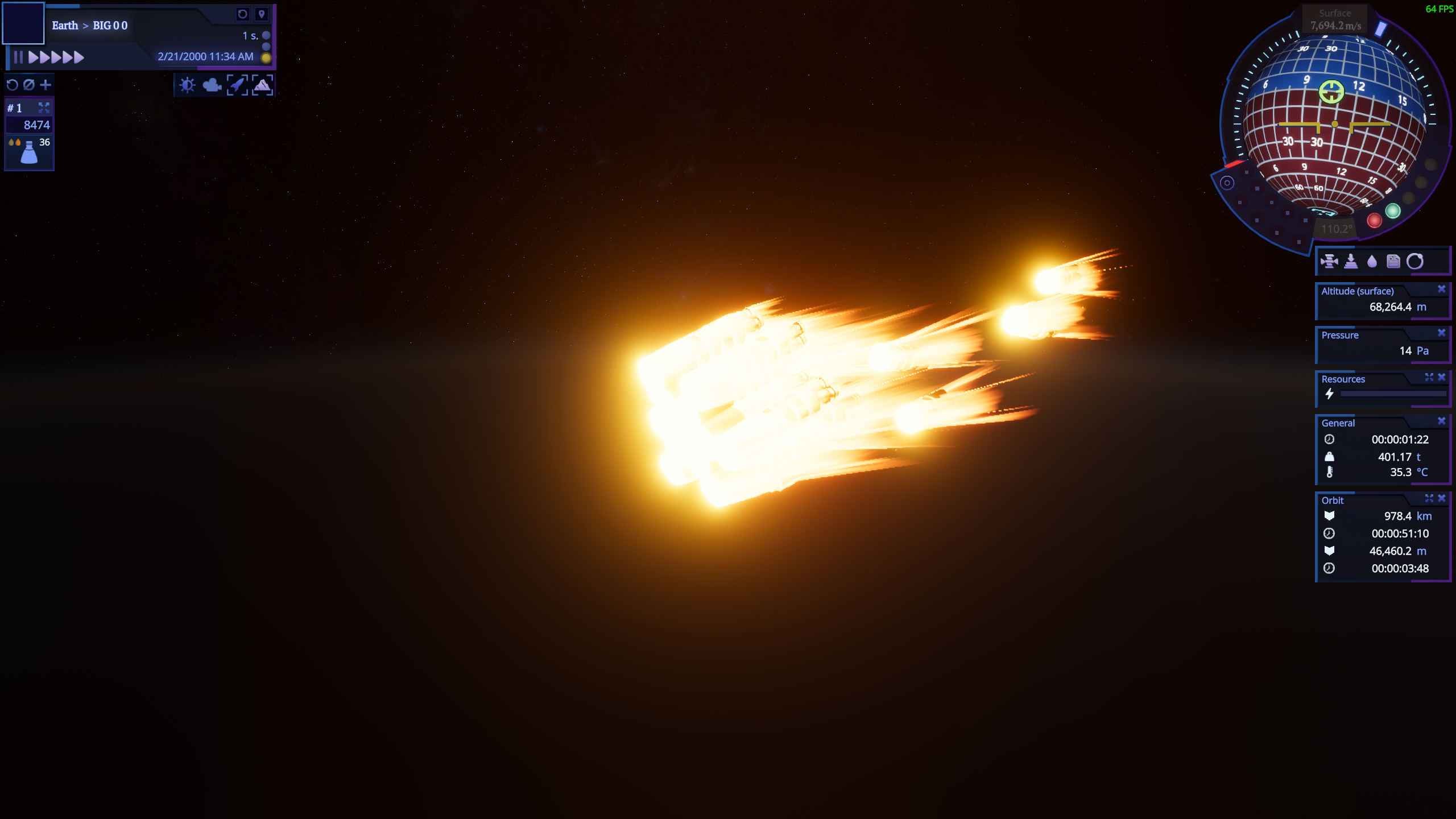

A re-entry shader made by using a shader graph

A re-entry shader made by using a shader graph

Finally, after almost two months of work, I could see a feature I wanted to implement initially working.  As always, there are a lot of things that need to be improved here, but it already feels good

As always, there are a lot of things that need to be improved here, but it already feels good

While burning dozens of spacecrafts in the atmosphere, I noticed that something was missing. Some parts heated too quickly, some others slower than I expected. It seems like only two parameters affected the gain of the temperature: surface area and mass (since at that point I set thermal capacity to equal values for all parts). But we have another important one: volume, and it didn’t affect thermodynamic processes at all.

Back to conductivity

After thinking a bit about this problem, I soon realized that heat should transfer not only between parts, but between surface and center of the part too. The quick way to do this, is define a part skin with the equal thickness everywhere. Since we already have an area of the part, we can calculate a skin volume and with the additional “skin density” parameter the skin mass. Then we could model heat transfer between skin and internals, approximating part as a sphere. Since we can calculate the volume of the part, then the average distance that heat should travel would be just this sphere’s radius. Very crude approximation, but it will get things done: introduce the dependance between how fast the part rises in temperature and its volume.

Also I needed to change almost all thermodynamics subsystems, because any heat transfer between the environment and the rocket would be through the skin. After that heat will go into internals. And only then parts will transfer it between each other’s internals.

I’ve made this change and got a lot of positive results. First of all, now I could observe thermal inertia. Environmental changes affected part internals much slower than skin. That, for example meant, that I could make a simple passive heat shield. I just need to set a very low thermal conductivity for it, and then it would take a very long time for the heat to raise the temperature of the heat shield itself and then to transfer to other parts.

But immediately after that new problem arose. Some rockets simply heated too slowly now to disintegrate in the atmosphere, even after I introduced maximum temperature for the skin. This is also because skin cooled down much faster via radiation due to its lower mass.

Back to re-entry heating

While doing a second research pass about re-entry heating, I found out two things: my chosen model underestimated heat flux on high speed and overestimated it on low one. Secondly, there are two parts in that process, convective and radiative heating. And I completely missed the second part. The effect of radiative heating becomes noticeable only at the speed of 9500 m/s and above, but it becomes exponentially bigger than convective heating at those speeds and above.

Relative Importance of Radiation vs Convection

Relative Importance of Radiation vs Convection

It literally took me the entire two days just to find how to calculate radiative heating without thousands of additional parameters and very expensive computations. But I finally found it thanks to “ANALYSES OF RADIATION AND CONVECTIVE HEATING OF FOUR TYPES OF DESCENDING SPACECRAFT” by С. T. Surzhikov and M. P. Shuvalov, one of few papers that were not locked by the paywall and contained exactly what I needed.

While correcting my model using new information I found, I also extended models of all currently present atmospheres for higher altitudes. As you know, atmospheric pressure doesn’t just disappear above 110 km. It decreases exponentially over thousands of kilometers, slowly approaching zero. While it makes sense not to use it for drag calculations, because the effect is very small and we need to get a stable orbit at some altitude, it may affect the temperature of spacecraft since you don’t need a physics simulation to calculate that. And even small pressure at high speeds doing it in a dramatic way. You will definitely notice these effects on a low Earth orbit.

Combining all of these changes, I finally got the feeling from the re-entry I wanted. And when returning from the Moon spacecraft without any thermal protection burned in seconds, I was very satisfied.

Convection

I will skip this section, because this article is already huge. Maybe I will tell about it another time, if someone would be interested reading about this. But long story short: it appeared even more complicated than everything I did before.

Performance

So how is the thermodynamics system performing? For tests I assembled 174 part spacecraft. While players built far bigger crafts (sometimes up to 5000 parts in total), this is a pretty big for the rocket when it enters the atmosphere thanks to staging.

This monstrosity is an average sized rocket on the launchpad

This monstrosity is an average sized rocket on the launchpad

I choosed atmosphere re-entry as a test case just because in this case every single thermodynamics system is working.

It burned pretty quickly, because it was a return from the Moon and radiative heating is pretty strong

It burned pretty quickly, because it was a return from the Moon and radiative heating is pretty strong

The results were not great, not terrible. It took around 0.3ms for the whole thermodynamics system on 1x physics time warp. So it could take up to 3ms on a 10x warp. The most expensive were re-entry subsystems, as I expected. It still will get 60 fps but if only one such spacecraft will be in the simulation. However I see a big potential for optimization there. For example I can try to multithread most of these calculations before the update release and see how it will change an overall performance.

The bigger problem appears when such a spacecraft enters the atmosphere at a shallow angle. It then will slowly disintegrate in hundreds of small pieces and each of them will end up in the physics simulation. They will quickly burn after that, but you will notice a stagger. I have some ideas, how it can be improved too.

Nothing unusual here, rocket is just falling apart

Nothing unusual here, rocket is just falling apart

While watching how spacecraft disintegrates is very satisfying, it brings up a whole new set of problems

While watching how spacecraft disintegrates is very satisfying, it brings up a whole new set of problems

Further work

While I’ve made a huge progress last month in thermodynamics development, there are still so many things to do. I tested the whole system on a small number of parts. Now I need to choose and set all newly added parameters for all rocket parts present in the game. Then I need to test differently assembled spacecrafts and see what kind of gameplay problems it will cause. After that I should finally make the tools, which will help players to solve all those problems, like heat shields, radiators or heaters. As for the visual component, I need to generate blob meshes for the re-entry effect for all parts too and tweak effect materials for most of them. And finally, I need to remake rocket part flight windows, so it not only will show the temperature of the part, but provide more capabilities, such as an ability to toggle almost every rocket part module, especially those that produce heat. Almost forgot, I need to make a tutorial, explaining the basics of thermodynamics and how to deal with it, otherwise frustration is guaranteed.

To summarize, I need another two or three weeks to finally finish thermodynamics and then to switch to flight UI improvements mentioned above. There are a lot of reported bugs by players waiting for my attention too. And a lot of new parts are sitting in the planned queue waiting to be implemented. And a bunch of QoL improvements I wanted to make in v0.22.0. There is a lot to do, so let’s not waste any more time and get to work.

Thanks for reading this and have a nice flight!

Discuss this article on Steam.